Deploying a Django app

May 30, 2020 | Categories: python django deployment tutorials

© Bulat Silvia | Dreamstime.com

Deploying an app is the process of making it suitable for a specific environment, getting it to run correctly in that environment for its users. Deployment is complicated and context-specific. This means there are many ways to go about it, depending on circumstances. This post tells you what you need to know so you can decide how to deploy your Django app.

So confusing! So many options! Where to start?

Django is a Python framework for creating web applications. It is so flexible that it’s the first choice for many beginners as well as a popular industrial framework used for complex web services by companies like Pinterest and Instagram. Django is attractive to beginners because it has great documentation and good community. Like other web frameworks it has its own development server, so you can test and run your code locally. But when it comes to moving Django projects online, because Django is so powerful, many complex options are available for large, commercial projects and it can be difficult for individuals building small personal projects to know where to start. Search terms like “how to deploy Django” come up with answers suitable for commercial projects maintained by teams of developers who use platforms such as Docker to deliver their Django apps. (Docker uses containers to smoothly deploy complicated, large codebases from development to production.) Individuals learning to code using Python and Django, building small portfolio apps, don’t need to use such complicated systems. The minimum you need is a domain name and an account with an appropriate, Python-friendly web-hosting service. Even so, there are multiple options for deployment: the rest of this page explains why deployment is not altogether straightforward and what that means for your options.

The mechanics of deployment

Web servers, like Apache and Nginx, provide HTTP request handling and serve static files. However, they don't usually talk directly to Python and run a Python app on their own; they use a go-between (an “application server”) to do that. GUnicorn, uWSGI and Phusion Passenger are such app servers. Many web hosting services provide cPanel, a suite of tools for web deployment, with a friendly web-based user interface. cPanel uses Passenger as its application manager and recommends deploying Python apps with Passenger and Apache. That is the software stack this tutorial series uses. To run an app, an app server must also know about the app’s existence: in order to deploy your app, you first register it with the app server. In other words, the app server has to know, when an HTTP request for a particular domain arrives, which app to run and where to find it. The app registration process makes this possible. Additionally, the app must be configured to tell the app server where to find the source code to run it and which version of Python to use. Django app writers do this using a wsgi (web server gateway interface) configuration inside each app. Django automatically provides a wsgi.py file in its app framework which works in a local environment, but the wsgi interface in production is specific to the production environment and must be configured accordingly. Your app needs a Passenger wsgi configuration file to tell the app server exactly which Python version to use and where to find the app's source code. A later page in this series shows you how to write the passenger_wsgi.py file for a Django app deployment using cPanel.

What are the choices?

Most deployment tutorials for individuals making small Django projects use PaaS, Platforms as a service, like Heroku or PythonAnywhere. Platforms like Heroku and PythonAnywhere are web hosts that automate app registration and configuration to make it easier for you. If you have a small Django app and you are using Django’s auto-generated SQLite database, using a PaaS for your first deployment might be a good option. They provide a user interface between you, your app and the web server and take you step-by-step through registration and configuration. They circumvent the difficulty of doing some of your own set-up and configuration and there are forums and some tech support in case you get stuck. The other option is to use a generic web hosting service. This would be preferable for the following reasons:

- You're already using a web host for other projects

- You want to understand the deployment process better (e.g.you want to work for a company using Django)

- You're using a more powerful, separate database, MySQL or PostgreSQL, and want access to your data without sole reliance on Django’s object-relational mapper (e.g. you want to use phpMyAdmin with MySQL)

- You want more control over deployment and production processes

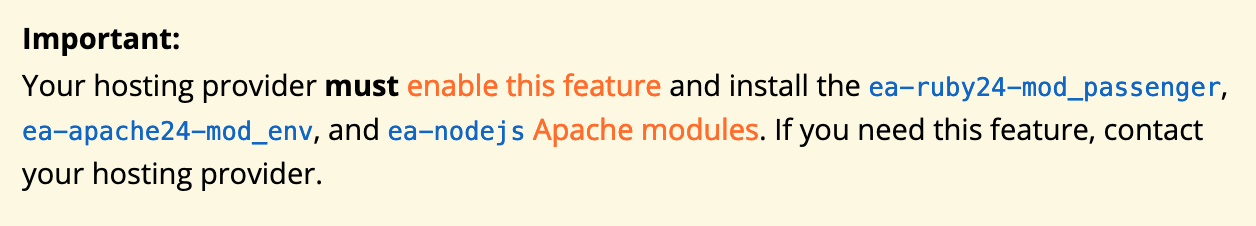

Not all web hosting services have an app server installed to run Python apps, so if you choose to run your Django app without using a PaaS, you should first find a web host that has an app server configured to run apps written in Python. I use Future Hosting, a cPanel web hosting provider who has Passenger configured to run Python apps. If you already have an account with a web host who does not have Passenger installed you can ask them to set it up. The relevant cPanel application manager documentation for them is here. Draw their attention to this box on that page:

Trying to run a Django app with cPanel without using an app server is not a joyful way forward. The cPanel wsgi documentation is here but it’s too terse to be useful, and also only works for python 2. The next four pages in this tutorial are a guide on how to deploy a Django app to a cPanel web host running Passenger:

- Upload your Django app to the web host

- Recreate your MySQL database remotely (optional)

- Register and configure your app for Passenger

- Troubleshoot Django deployment

The tutorial assumes that you have already built and tested a Django web app on your personal computer (your local environment). By the end of the series you will see your Django app in the browser at its domain name url. Perhaps more importantly, you will understand the basics of how the app runs in a production environment and how to troubleshoot common problems in deployment.

*** Was this page useful? How could it be better? I'm grateful for suggestions. Please DM me @_awbery_on Twitter with feedback. Thank you!